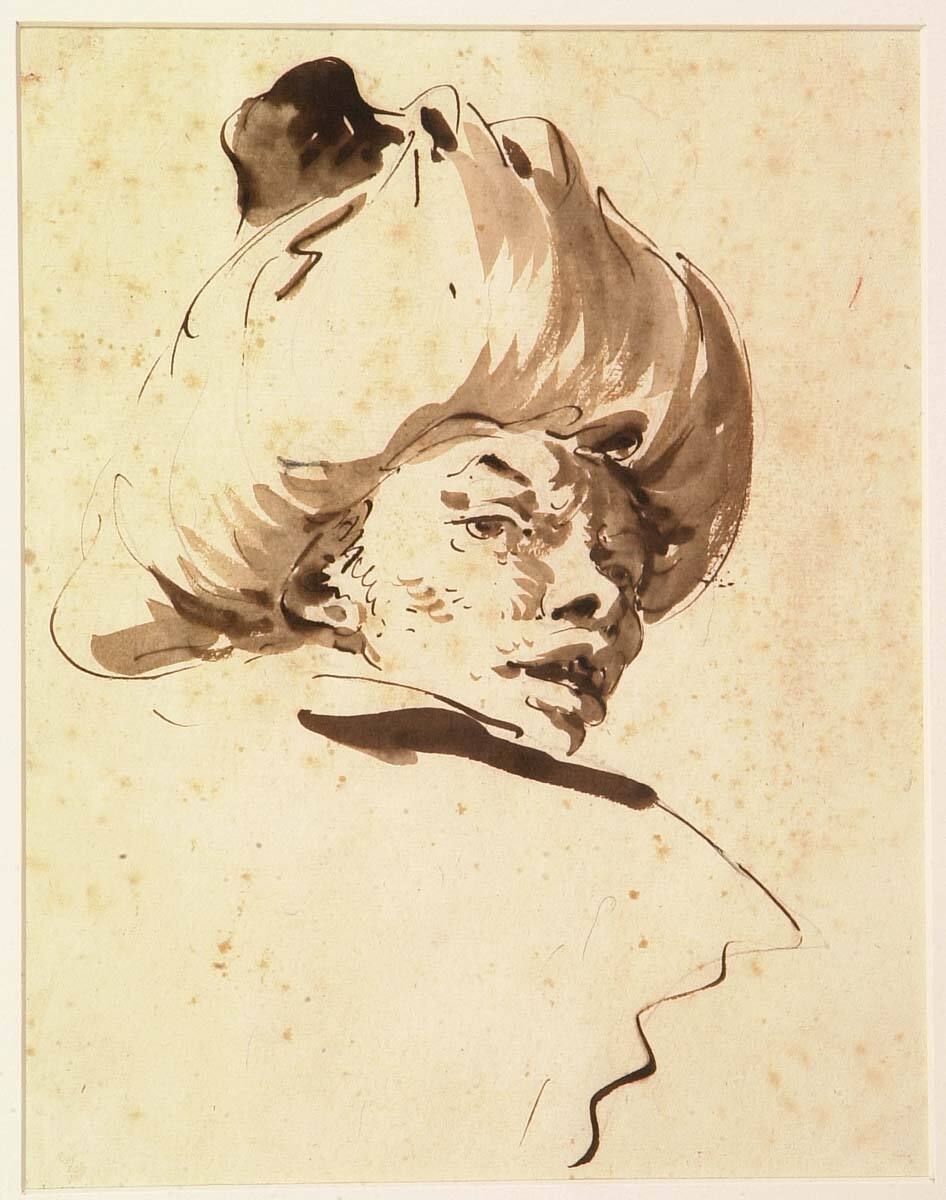

Head of a Roebuck

Framed: 22 3/4 x 18 3/4 x 1 1/4 inches (57.79 x 47.63 x 3.18 cm)

Albrecht Dürer Ausstellung, Germanisches Museum, Nuremberg, April-September 1928, no. 387.

Drawings and Prints by Albrecht Dürer, The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York, March 17-April 16, 1955, unnumbered, as Head of a Roebuck.

Great Master Drawings of Seven Centuries: A Benefit Exhibition of Columbia University for the Scholarship Fund of the Department of Fine Arts and Archaeology, Knoedler and Company, New York, October 13-November 7, 1959, no. 25, as Head of a Roebuck.

Dürer in America: His Graphic Work, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., April 25-June 6, 1971, no. XI, as Head of a Roebuck.

Gothic and Renaissance Art in Nuremberg, 1300-1550, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, April 8-June 22, 1986; Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, July 24-September 28, 1986, no. 112, as Head of a Roebuck.

Dürer to Matisse: Master Drawings from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, The Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, OK, June 23-August 18, 1996; The Cummer Museum and Gardens, Jacksonville, FL, September 20-November 29, 1996; The Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, December 21, 1996-March 2, 1997, no. 3, as Head of a Roebuck.

Dürer to Matisse: Master Drawings from the Permanent Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, July 12-September 6, 1998, no cat., as Head of a Roebuck.

Dürer to Tiepolo: Works on Paper, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 12, 2012-June 9, 2013, no cat., as Head of a Roebuck.

Albrecht Dürer, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, July 17-January 12, 2019-2020.

Prince Henryck Lubomirski (1777-1850), Przeworsk (present-day Poland), by 1834-1850 [1];

By descent to his son, Jerzy Henryk Lubomirski (1817-1872), Przeworsk, 1850-July 10, 1866;

Transferred to the Lubomirski Museum, Ossolinski National Institute, L’viv (present-day Ukraine), July 10, 1866-July 2, 1941 [2];

Confiscated from the Lubomirski Museum by German National Socialist (Nazi) forces, July 2, 1941-May 1945 [3];

Recovered by Allied forces and taken to the Munich Central Collecting Point, May 1945-May 26, 1950 [4];

Restituted by Allied forces to Prince Georg Lubomirski (1887-1978), Geneva, May 26, 1950-December 9, 1953 [5];

Purchased from Lubomirski, through Paul Drey, Inc., by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1953.

NOTES:

[1] When inventoried as part of Lubomirski’s collection in 1834, this drawing was part of a group of 27 Dürer drawings on 24 sheets (three were double-sided).

[2] An 1823 agreement between Prince Henryk Lubomirski and the founder of the Ossolinski National Institute, Count Józef Maksymilian Ossolinski, stated that Lubomirski would donate his library and art collections to the Ossolinski National Institute to be housed in a Lubomirski Museum. The works were finally transferred to the Institute in 1869, under a foundation charter that maintained the Lubomirski family’s right of inheritance to the objects in a hereditary estate, under which direct Lubomirski descendants would be “literary curators”. If in the future, the Ossolinski National Institute were dissolved, its funds used for purposes other than those stated in the charter, or the literary curator’s rights limited in any way, the Lubomirski collection would revert to the Lubomirski hereditary estate. If such a breach occurred, the relationship between the Ossolinski National Institute and the Lubomirski Museum could be restored, under the original conditions, within 50 years. If the Lubomirski hereditary estate was abolished by governmental authority, the contents of the Lubomirski Museum would become the unencumbered property of the heir’s family. For more information, see Ossolinski National Institute, The Fate of the Lubomirski Dürers (Wroclaw: Society of the Friends of the Ossolineum, 2004), 9-16 and Konstantin Akinsha and Sylvia Hochfield, “Who Owns the Lubomirski Dürers?” in ARTnews, 100, no. 9 (October 2001), 158-163.

[3] This drawing, along with the other Lubomirski Dürers, was removed from the Lubomirski Museum July 2, 1941 by Kajetan Mühlmann, the Nazi officer in charge of art confiscation in Poland and Holland, on direct orders from Hermann Göering, Reichsmarschall and head of the Luftwaffe, to whom Mühlmann handed over the drawings on July 3, 1941. They were intended for the planned Führermuseum in Linz and this drawing was assigned Linz inventory number 1984/23. They were sent to Berlin and delivered to Adolf Hitler, who admired them so much he frequently kept them in his possession, even when he traveled to his Eastern Front headquarters. The Dürers were eventually deposited in the Alt Aussee salt mine art repository in Austria in early 1945, where this drawing was assigned number 1743. Copies of Allied and German documents describing the drawing’s wartime movements are in the NAMA curatorial files. For Mühlmann’s own account of the confiscation of the Dürer drawings from L’viv, see Bundesarchiv, Koblenz, B323/332, Aussagen und Erklärungen von Händlern und Verkäufern (K-Z) (1946) 1949-1961.

[4] Following the discovery of the artworks in the mine by Allied forces in May 1945, this drawing entered the Munich Central Collecting Point on July 4, 1945, where it was given inventory number 2399-232.

[5] Allied restitution policy, drawn up at the Potsdam Conference in 1945, directed all recovered art works to be returned to their countries of origin. The governments of those countries would restitute the objects to the individual rightful owners. By 1948, as the new Cold War progressed and it became clear that restitution by the Soviet Union was improbable, this policy changed to allow people who had fled Soviet-occupied countries to make their claims directly to the Allies. In July 1948, Prince Georg Lubomirski, grandson of Prince Henryk, submitted a claim for the Dürer drawings. Based on the 1869 Lubomirski-Ossolinski agreement, the U.S. State Department returned the Dürer drawings to Prince Georg Lubomirski on May 26, 1950. This decision was the result of a number of complicated factors: the failure of the USSR and Poland to file claims for the drawings after the war, the new location of L’viv within the USSR following the redrawing of Poland’s borders at the Potsdam Conference, and Poland’s dissolution of hereditary estates in 1946.

Kayetan Vinzenz Kielisinskik, Inventory of the Graphic Collection (Przeworsk (present-day Poland): Lubomirski Archive, 1834).

Ladislaus Lusczkiewicz, Inventory of 1869 (Warsaw: Archives of the Ossilineum, 1869).

Friedrich Winkler, “Der Lemberger Dürerfund,” Der Kunstwanderer (May 1927): 354.

Albrecht Dürer Ausstellung im Germanischen Museum, exh. cat. (Nuremberg: Germaniches Museum, 1928), 5.

Hans Tietze, Kritisches Verzeichnis de Werke Albrecht Dürers, vol. 1, Der junge Dürer (Augsburg, Germany: Filser, 1928), no. 197a, p. 17.

Friedrich Winkler, “Dürerstudien I, Dürers Zeichnungen von seiner ersten italienischen Reise (1494-95),” Jahrbuch der preussischen Kunstsammlungen 50 (1929): 137, (repro.).

Mieczysław Gębarowicz and Hans Tietze, Albrecht Dürers Zeichnungen im Lubomirski-Museum in Lemberg (Vienna: Anton Schroll, 1929), 8.

Friedrich Lippmann, Zeichnungen von Albrecht Dürer in Nachbildungen, vol. 7 (Berlin: Grote, 1929), no. 894, pp. 27-28, (repro.), as Kopf eines Rehbocks.

Eduard Flechsig, Albrecht Dürer: Sein Len und Leben und seine künstlerische Entwicklung, vol. 2 (Berlin: Grote, 1931), 475.

Friedrich Winkler, Die Zeichnungen Albrecht Dürers, vol. 2, 1503-1510/11 (Berlin: Deutscher Verein für Kunstwissenschaft, 1937), no. 364, p. 79, (repro.), as Kopf eines Rehbocks.

Hans Tietze and Erica Tietze-Conrat, Kritisches Verzeichnis de Werke Albrecht Dürers, vol. 2, Der reife Dürer, pt. 2 (Basel: Holbein Verlag, 1937-38), no. A342, p. 120, 154, (repro.).

Erwin Panofsky, Albrecht Dürer, vol. 2 , 2nd ed.(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1945), no. 1349, p. 131, as Head of a Roebuck.

“Dürerzeichnungen gehen nach Amerika,” Die Neue Pallas: Internationaler Wissenschaftlicher Nachrichtendienst 19, no. 27 (April 1954): unpaginated.

n.a, “Dürer geht über den Ozean,” Die Weltkunst 24 (May 15, 1954): 6.

Felice Stampfle, Drawings and Prints by Albrecht Dürer, exh. cat. (New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 1955), 6, 10, as Head of a Roebuck.

Friedrich Winkler, Albrecht Dürer: Leben und Werke (Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1957), 182.

Great Master Drawings of Seven Centuries: A Benefit Exhibition of Columbia University for the Scholarship Fund of the Department of Fine Arts and Archaeology, exh. cat. (New York: Knoedler and Company, 1959), 32-33, (repro.), as Head of a Roebuck.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 85, (repro.), as Head of a Roebuck.

Ira Moskowitz, ed., Great Drawings of All Time, vol. 2, German, Flemish, and Dutch: Thirteenth through Nineteenth-Century (New York: Shorewood Publishers, 1962), unpaginated.

Mahonri Sharp Young, “The Loving Eye, the Cunning Hand,” Apollo 94, no. 113 (July 1971): 44, (repro.).

Charles W. Talbot, ed., Dürer in America: His Graphic Work, exh. cat. (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1971), 48-49, (repro.), as Head of a Roebuck.

Alan Shestack, “Dürer’s Graphic Work in Washington and Boston,” The Art Quarterly 35 (1972): 303.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 176, 180, (repro.), as Head of a Roebuck.

Walter L. Strauss, The Complete Drawings of Albert Dürer, vol. 1 (New York: Abaris Book, 1974), no. 1495/46, p. 352, (repro.).

Fedja Anzelewsky, Dürer: His Art and Life, trans. Heide Grieve (New York: Alpine Fine Arts Collection, 1980), 106, (repro.), as Head of a Stag.

Fritz Koreny, “Albrecht Dürers Studien eines Rehbocks in Bayonne und Kansas City. Bemerkungen zu einer nachtraglich geteilten Zeichnung,” Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen in Wien 82/83 (Neue Folge Band XLVI/XLVII) (1986-1987): 11-15, (repro.), as Kopf eines Rehbocks.

Martin Angerer et al., Gothic and Renaissance Art in Nuremberg, 1300-1550, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986), 282, (repro.), as Head of a Roebuck.

Fritz Koreny, Albrecht Dürer and the Animal and Plant Studies of the Renaissance, exh. cat. (New York: New York Graphic Society, 1988), 158, (repro.), as Head of a Roebuck.

Colin Eisler, Dürer’s Animals (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), 104, 343, (repro.), as Head of a Roebuck.

Martin Bailey, “The Lubomirski Dürers: Where Are They Now?” The Art Newspaper 7, no. 48 (May 1995): 5.

Roger Ward, Dürer to Matisse: Master Drawings from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1996), 14, 40-42, (repro.), as Head of a Roebuck.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 56, (repro.), as Head of a Roebuck.

Jochen Sander, Albrecht Dürer: His Art in the Context of its Time, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel, 2013).