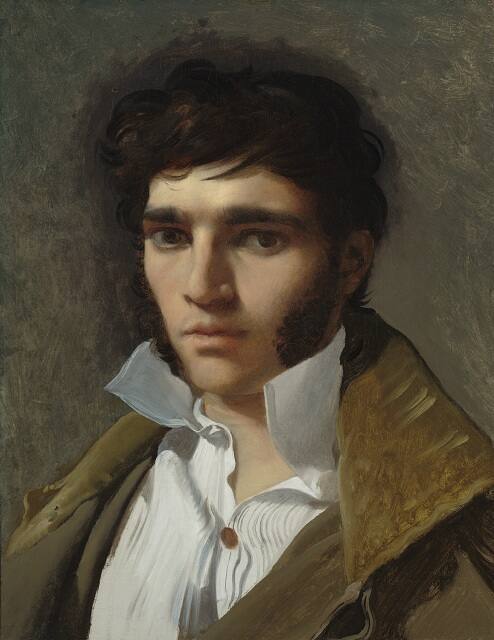

Portrait of the Marquise d'Usson de Bonnac

Framed: 67 × 53 1/2 × 5 7/8 inches (170.18 × 135.89 × 14.92 cm)

- 118

In the possession of the sitter, Esther d’Usson (née de Jaussaud or Jossaud, dame de Tarabel, 1654–1750), 1st Marquise de Bonnac, Château de Bonnac and Tarabel, France, 1707–1750 [1];

Paul Friedrich Meyerheim (1842–1915), Berlin, by 1896–September 14, 1915 [2];

Purchased at his posthumous sale, Nachlass Paul Meyerheim, Rudolph Lepke’s Kunst-Auctions-Haus, Berlin, March 14, 1916, lot 92, erroneously as by Alexandre Roslin, Weibliches Bildnis;

Purchased on the U.S. art market by an unknown private collector, ca. 1967 [3];

Purchased from the private collector, through Leonardo Lapiccirella, by Heim Gallery, London, stock no. 30/77, by November 1976 [4];

Purchased from Heim by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1977.

Notes

[1] The Marquise’s husband Salomon d’Usson de Bonnac, Marquis de Bonnac, died in 1698, and the following year she was briefly confined in an Ursuline convent at the insistence of her brother-in-law, Tristan Dusson de Laquère. But in 1702, the Marquise returned to Tarabel, where she had been born and raised. It was while she was living there that the portrait was painted in 1706–1707. It is plausible that she visited Paris for her portrait sitting. The painting may have been commissioned by her son, Jean Louis d’Usson, Marquis de Bonnac, with whom she lived, at rue de Grenelle in Paris from 1710 to 1739. After his death in 1738, she returned to Tarabel to live with her granddaughter, Constance Françoise Wignacourt, where she died in June 1750, at around 96 years of age. See “2 E 10982, Tarabel. 1 E 6 bis registre paroissial: BMS (collection communale), (1635-An V),” Departmental Archives, Haute-Garonne, Toulouse.

Inventories of the offspring of Salomon and Esther d’Usson, Marquis and Marquise de Bonnac, in the National Archives, Paris, do not cite the Nelson-Atkins painting in lists of family property. See T/1042/3, “Lettres, mémoires, comptes, contrats de mariage, papiers divers relatifs à la famille d’Usson depuis le Moyen-Âge et au marquis de Bonnac,” Archives Nationales, Paris. See correspondence between Glynnis Stevenson, NAMA, and Lauranna Favasuli, doctoral researcher on the d’Usson de Bonnac family, and Myriam Daydé, specialist in medieval archaeology and history based in Toulouse, France, September 2022, NAMA curatorial files.

See Stéphan Perreau’s entry on the (now lost) painting of Edmée d’Hozier (née Terrier), in Perreau, Catalogue Raisonné des Oeuvres de Hyacinthe Rigaud (2016): http://www.hyacinthe-rigaud.com/catalogue-raisonne-hyacinthe-rigaud/portraits/1685-terrier-edmee, where he suggests that the Marquise de Bonnac asked the artist to use the same format as that used in d’Hozier’s portrait, which the former would have seen from sketches kept in Rigaud’s studio. See also Hyacinthe Rigaud, Livres de raison, Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France, Paris, from the collection of the magistrate and bibliophile Antoine Moriau (1699–1759) and the Bibliothèque de la Ville de Paris: Ms. 624 (Mémoire, par année, des portraits ou copies exécutées par Rigaud ou par ses soins, avec prix en regard [1681–1743]), fol. 26, as “Made La marquise d’Usson de Bonnac, 500 lt” [livres tournois]; and Ms. 625 (Mémoire, par année, des copies que fit exécuter Rigaud, avec indication des artistes employés et de leurs honoraires [1694–1725]), fol. 21 (1706 Monmorency, as “Ebauché l’habit du portrait de la mère de mr de Bonnac, 8 lt”).

[2] The painting appears in a photograph of Paul Meyerheim’s music room from 1896; see Hermann Rückwardt, Ausgeführte Architekturen in Berlin von Alfred Messel (Leipzig: Gross Lichterfelde, 1896), pl. 17.

[3] According to A. S. Ciechanowiecki, Heim Gallery, London, in a letter to Ross Taggart, April 19, 1977, NAMA curatorial files, the unknown private collector purchased the painting in the U.S. “about ten years ago,” then sold the painting indirectly to Heim on the Continental art market “quite recently.” In early 1978, the Kansas City Star reported that the painting was purchased from a Chicago collection, although that could be a reference to Mary Withers Runnells (1892–1977), who lived in Lake Forest, IL, and financially supported the purchase but never owned the painting. See Marietta Dunn, “Rigaud to Gallery,” Kansas City Star 98, no. 130 (January 29, 1978): 3E.

[4] The name “Lapiccirella” appears here: “July 28, 1977,” Heim Gallery Commission Book, 1970–1988, Heim Gallery Records, Series V.A, Financial, Stockbooks, Box 202, folder 6, Special Collections, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

Hermann Rückwardt, Ausgeführte Architekturen in Berlin von Alfred Messel: photographische Original-Aufnahmen nach der Natur; in Lichtdruck Herausgegeben von Hermann Rückwardt (Leipzig: Gross Lichterfelde, 1896), pl. 17, (repro).

Paul Eudel, Les Livres de comptes de Hyacinthe Rigaud (Paris: Librairie H. Le Soudier, 1910), 72, 170, as Mme La Marquise Dorson [sic] de Bonnac.

Nachlass Paul Meyerheim Berlin; 1. Abteilung: Der künstlerische Nachlass Des Meisters, Gemälde des 16.–18. Jahrhunderts; 5 Werke von A. v. Menzel und zahlreiche Arbeiten anderer Künstler des 19. Jahrhunderts; Versteigerung 14. und 15. März 1916 (Berlin: Rudolph Lepke’s Kunst-Auctions-Haus, March 14–15, 1916), 12, (repro.), erroneously as by Alexandre Roslin, Weibliches Bildnis.

“Kunstausstellungen Berlin: Sammlung Paul Meyerheim,” Kunst und Künstler 14 (1915–16): 416, erroneously as by A. Roslin, weibliches Bildnis.

“Der Kunstmarkt—Versteigerungen,” Der Cicerone, no. 5–6 (March 1916): 114.

“Berlin,” Der Kunstmarkt, no. 23 (March 3, 1916): 97–98, (repro.), erroneously as by Alexandre Roslin, Weibliches Bildnis.

“Nachlaß Paul Meyerheim, Berlin. I. Abteilung: Der künstlerische Nachlaß des Meisters. Gemälde des 16. bis 18. Jahrh. und Arbeiten anderer Künstler des 19. Jahrh. Versteigerung am 14. und 15. März 1916 bei Rudolph Lepke, Berlin,” Der Kunstmarkt, no. 27 (March 31, 1916): 114, erroneously as by Alex. Roslin, Weibliches Bildnis.

“Vom Kunstmarkt.,” Internationale Sammler-zeitung, no. 9 (May 1, 1916): 87, erroneously as by Alex. Roslin, Weibliches Bildnis.

J[oseph] Roman, Le Livre de Raison du peintre Hyacinthe Rigaud (Paris: Henri Laurens, 1919), 130, 132, as Made la marquise d’Usson de Bonnac.

“Heim: Old Master Paintings and Sculptures advertisement,” Burlington Magazine 118, no. 885 (December 1976): lxi, (repro.), as Portrait of the Marquise d’Usson de Bonnac.

Marietta Dunn, “Rigaud to Gallery,” Kansas City Star 98, no. 130 (January 29, 1978): 3E, (repro.), as Portrait of the Marquise d’Usson de Bonnac.

Roger B. Ward, Dürer to Matisse: Master Drawings from the Nelson-Atkins, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1996), 117, as Portrait of the Marquise d’Usson de Bonnac.

Alvin L. Clark, Jr., ed., Mastery and Elegance: Two Centuries of French Drawings from the Collection of Jeffrey E. Horvitz, exh. cat. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Art Museums, 1998), 156, 365n5, (repro.), as Portrait of the Marquise d’Usson de Bonnac.

Dominique Brême, “‘Personne n’a poussé plus que lui l’imitation de la nature,’” exh. cat., L’Estampille: L’Objet d’Art, special issue (2000): 42.

Neil Jeffares, “The Marquis de Bonnac: a suggested identification of a portrait by Louis Vigée,” British Journal for Eighteenth Century Studies 25 (2002): 49, 70n18.

Ariane James-Sarazin, “Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659–1743)” (PhD diss., École Pratique des Hautes Etudes, 2003; Lille: Atelier national de reproduction des thèses, 2008), 2, pt. 3: no. 834, pp. 1315–16, (repro.), as Made la marquise d’Usson de Bonnac.

Piero Boccardo, Clario Di Fabio, and Philippe Sénéchal, Genova e la Francia: Opera, artisti, committenti, collezionisti, exh. cat. (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2003), 218.

Sven Kuhrau, Der Kunstsammler im Kaiserreich: Kunst und Repräsentation in der Berliner Privatsammlerkultur (Kiel, Germany: Verlag Ludwig, 2005), 72, 281, (repro.), erroneously as by Alexander Roslin, weibliches Bildnis.

Stéphan Perreau, Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659–1743): catalogue concis de l’œuvre (Sète, France: Nouvelles Presses de Languedoc, 2013), no. PC.973, p. 205, (repro.), as Portrait de Esther de Jaussaud, marquise d’Usson de Bonnac.

Neil Jeffares, “Vigée, Le marquis de Bonnac,” Pastels and Pastellists (February 3, 2016): http://www.pastellists.com/Essays/Vigee_Bonnac.pdf#search=%22bonnac%22, 3, as Made la marquise d’Usson de Bonnac.

Neil Jeffares, “Usson de Bonnac,” Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800, Online edition, Iconographical genealogies (December 29, 2016): http://www.pastellists.com/Genealogies/Usson.pdf.

Ariane James-Sarazin, Hyacinthe Rigaud 1659–1743: L’homme et son art and Catalogue raisonné (Dijon: Éditions Faton, 2016), no. P.1005, pp. 1:474, (repro.); 2:170, 335, 608, (repro.), as Esther d’Usson de Bonnac, née de Jaussaud.

Stéphan Perreau, Catalogue raisonné des œuvres de Hyacinthe Rigaud (2016): http://www.hyacinthe-rigaud.com/catalogue-raisonne-hyacinthe-rigaud/portraits/1272-jaussaud-esther-de, no. PC.973, as Esther de Jaussaud, or as Madame d’Usson de Bonnac, and mentioned under nos. P.504, PC.625, and P.1217.

Ariane James-Sarazin, “Ni tout à fait la marquise de Croissy, ni tout à fait Mme d’Usson de Bonnac,” Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659–1743): L’homme et son art; Le catalogue raisonné, online edition by Editions Faton (March 24, 2018): http://www.hyacinthe-rigaud.fr/single-post/2018/03/24/Ni-tout-a-fait-la-marquise-de-Croissy-ni-tout-a-fait-Mme-dUsson-de-Bonnac.

Kristie C. Wolferman, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A History (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2020), 262–63, (repro.), as Portrait of the Marquise d’Usson de Bonnac.

Joseph Baillio, “Hyacinthe Rigaud, Portrait of Esther d’Usson (née de Jaussaud or Jossaud, dame de Tarabel), Marquise de Bonnac, 1706–1707,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.328.5407.