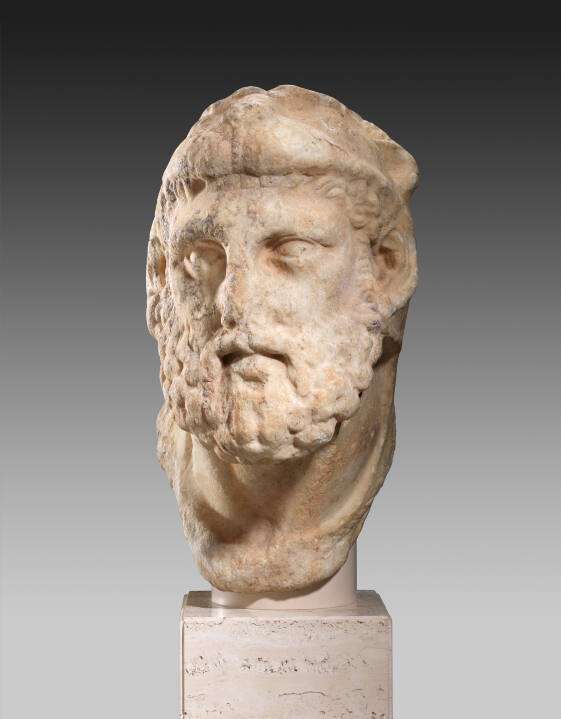

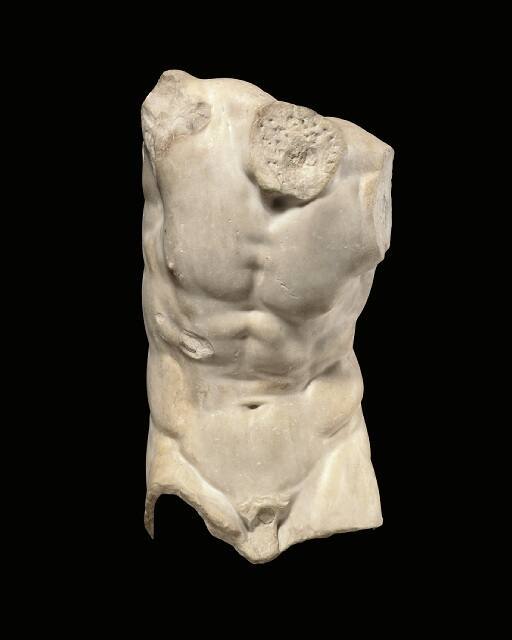

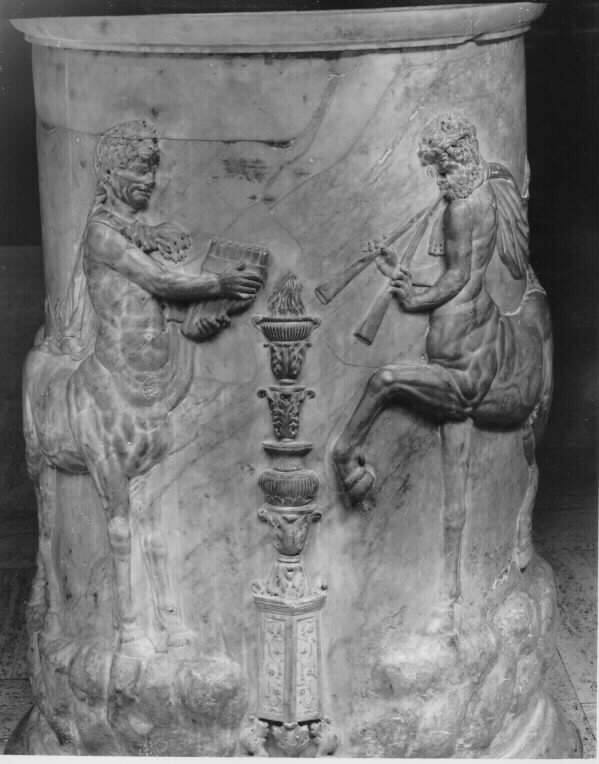

Portrait of Antinous (?)

- 103

Roman Portraits, Worcester Art Museum, MA, April 6-May 14, 1961, no. 173.

This portrait may be of Antinous, the lover of the emperor Hadrian (his portrait appears to your right beyond the niche). Antinous, a youth from Asia Minor (modern Turkey), met Hadrian on one of the emperor’s many travels East and became his constant companion. The youth drowned in the Nile in October 130 c.e. Deeply grieved by Antinous’s death, Hadrian declared that the youth had become a god, and he had temples with portraits of the boy set up throughout the Roman Empire.

Found in Italy [1];

With Pietro Stettiner (1855-1920), Rome, by 1920 [2];

Ludwig Pollak (1868-1943), Vienna and Zürich, by 1938-1943 [3];

By inheritance to his sister-in-law, Margarete Süssmann Nicod (d. 1966), Zürich, 1943-1953;

Purchased from Nicod, through Harold Woodbury Parsons, by the dealer Jacob Hirsch (1874-1955), New York, 1953-1955 [4];

Purchased from Hirsch by an unknown private collector, Zürich, 1955 [5];

With Paul and Margot Mallon, New York, by 1959;

Purchased from Paul and Margot Mallon by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1959.

NOTES:

[1] According to Margot Mallon, in a letter to Ross Taggart, NAMA, March 17, 1959, NAMA curatorial files.

[2] John Marshall Archive, British School at Rome, cardfile B.I.23, and Deutsches Archaeologisches Institut, Rome, photoarchive. It is possible Pollak acquired the sculpture from Stettiner, whom he had known for many years, but the circumstances of Pollak’s purchase of the sculpture are currently unknown.

[3] Ludwig Pollak, a Jewish art historian and dealer, was murdered by the Nazis in Auschwitz in 1943. For more on Pollak as a connoisseur and art dealer in Rome, see Margarete Merkel Guldan, Die Tagebücher von Ludwig Pollak. Kennerschaft und Kunsthandel in Rom 1893-1934 (Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1988).

[4] The Nelson-Atkins’s European art agent, Harold Woodbury Parsons, wrote to Director Laurence Sickman in a letter dated April 9, 1962: “[In] the winter of 1938, I was en passant in Rome and saw Pollak. At that time he showed me the photographs of five or six sculptures he told me he had set aside for his old age and they had been for years in a case in a storage warehouse in his native Vienna. These he was now prepared to sell; and as he knew I was collecting for the Gallery…he would show them to me, in Vienna, next season when I came abroad. The objects included the Antinuous bust…but I did not return to Italy in 1939 as war clouds were gathering and, of course, I never saw Dr. Ludwig Pollak again…After I was retired and settled in Rome in 1953, I received one day, to my great surprise, a letter from an unknown female cousin of the late Dr. Pollak…She had come across a letter of mine to him, shortly before he and his family were deported by the Nazis. I went to see her and she told me that in 1939, seeing which way the wind was blowing, her late cousin had taken the case containing the sculptures to Zürich and had deposited it in a bank-vault there. She asked me to go to see the objects…and help her dispose at once of the pieces…Hirsch was in Paris and, at my suggestion, bought the whole group.” NAMA Archives, MS001 Laurence Sickman Papers, Box 1c, Harold W. Parsons 1947-1964. The female cousin Parsons refers to was in fact Nicod, who was actually the sister of Pollak’s second wife, Julia.

Jacob Hirsch, PhD. (1874–1955) was born in Munich,

studied at Deutsches Archäologisches Institut in Rome, and then founded a

dealership in Munich in 1897. He moved to Lucerne in 1919 and founded Ars

Classica in 1922. In 1931, he opened Jacob Hirsch Antiquities in New York. At

some point, he also had a gallery in Paris. He handled coins and antiquities

but also had his own collection. See Hadrien Rambach, “A List of coin dealers

in nineteenth-century Germany,” in A Collection in Context. Kommentierte Edition der Briefe und

Dokumente Sammlung Dr. Karl von Schäffer, ed. Henner Hardt and Stefan Krmnicek

(Tübingen, Germany: Tübingen University Press, 2017), 69–70, hal-04345662. See also “Dr. Jacob

Hirsch, 81, An Authority on Art,” New York Times, July 5, 1955, 29.

[5] According to Harold Woodbury Parsons, in a letter to William Milliken, July 14, 1955, Cleveland Museum of Art Archives, Office of the Director’s Records, Series II, Box 66, Folder 15.

Anton Heckler, Römische Bildnisstudien La Critica d’Arte 3 (1938): 92-93, plate 58, figs. 3, 4.

Hans Weber, “Eine spätgriechische Jünglinsstatue,” in V. Berichte über die Ausgrabungen in Olympia, ed. Emil Kunze (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1956), 132n19.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 39.

Cornelius Vermeule, “Antinous, Favorite of the Emperor Hadrian,” Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 3, no. 2 (October 1960): 1-7.

Michael Milkovich, Roman Portraits, exh. cat. (Worcester, MA: Worcester Art Museum, 1961), 42-43, no. 173.

Christoph Clairmont, Die Bildnisse des Antinous. Ein Beitrag zur Porträtplastik unter Kaiser Hadrian, Bibliotheca Helvetica Romana 6 (Rome: Istituto Svizzero di Roma, 1966), 14n2, 15n1, 21, 29n3, 35-36, 54, no. 48, plate 31, fig. 48.

Jörgen Bracker, review of Die Bildnisse des Antinous. Ein Beitrag zur Porträtplastik unter Kaiser Hadrian by Christoph Clairmont, Bonner Jahrbücher 170 (1970): 554.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 49.

David Thompson, “The Lost City of Antinous,” Archaeology 34, no. 1 (1981): 45.

Cornelius Vermeule, Greek and Roman Sculpture in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981), 312-13, no. 269.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 121.

Klaus Fittschen, Prinzenbildnisse antoninischer Zeit, Beiträge zur Erschließung hellenistischer und kaiserzeitlischer Skulptur und Architektur 18 (Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1999), 81, no. 12, plate 133 a-b.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 17, fig. 45.

Orietta Rossini, ed., Ludwig Pollak: Archaeologist and Art Dealer, exh. cat. (Rome: Gangemi Editore spa, 2019), 171.