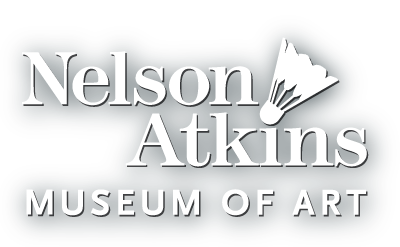

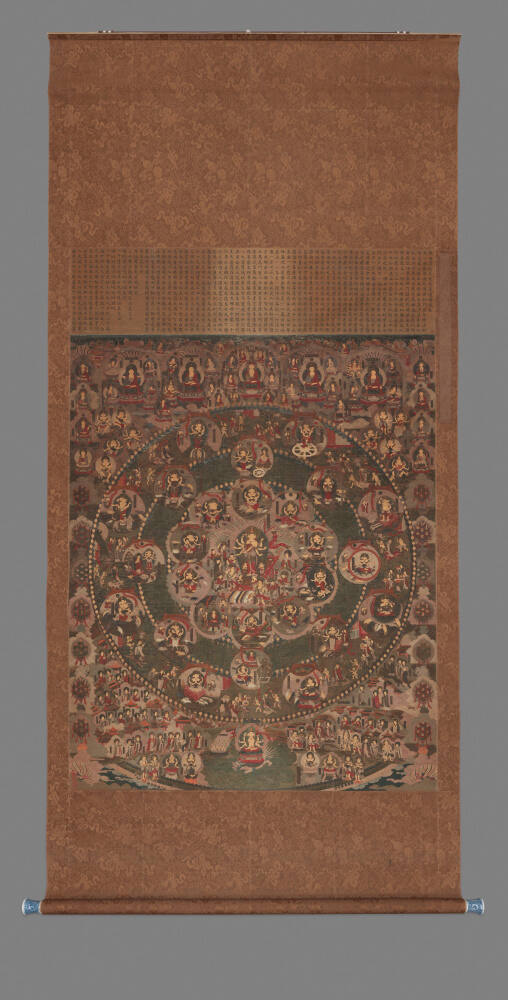

The Assembly of Tejaprabha

- 230

Tejaprabha sits here on a lotus throne surrounded by a constellation of figures representing the Eleven Celestial Luminaries-the Sun, Moon, and Five Planets of traditional Chinese astronomy and the four imaginary Dark Stars. The painting technique uses strong sweeping outlines of black ink, filled with bright mineral colors, particularly cinnabar red and malachite green, with a subtle use of blue highlights. The figures are solemn and substantial, counterbalanced by fluid drapery lines, flying scarves and transparent haloes that give the mural a sense of light gracefulness and intense, but restrained, energy.

Guangsheng Monastery, Hongdong, Shanxi province, China, early 14th century-probably 1927 [1];

With C. T. Loo & Co., Paris and New York, by 1930-1932 [2];

Purchased from C. T. Loo & Co. by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1932.

NOTES:

[1] This painting was installed on the west wall of the main hall, the Mahavira Hall (Daxiong baodian), of the Guangsheng monastery’s lower temple, where it stood opposite a mural depicting Bhaishajyaguru (today in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, no. 65.29.2). A stele in the temple, dated 1929, described how the temple’s abbot sold paintings from the temple in 1927 to raise funds for repairing the building. For more about the mural’s history, see among others, Ling-en Lu, “Pigment Style and Workshop Practice in the Yuan Dynasty Wall Paintings from the Lower Guangsheng Monastery” in Original Intentions: Essays on Production, Reproduction, and Interpretation in the Arts of China, eds. Nick Pearce and Jason Steuber (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2012), 74-137and Aschwin Lippe, “Buddha and the Holy Multitude,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 23, no. 9, part 1 (May 1965): 325-35.

[2] C. T. Loo first mentioned this mural in a letter to J. C. Nichols, Nelson-Atkins Trustee, dated December 25, 1930, Nelson-Atkins Archives, RG80/10, Box 2, Folder 3. The Nelson-Atkins purchased the mural in 1932 as part of a plan to assemble a Chinese temple period room. For more regarding the Nelson-Atkins’s purchase of the mural, see Ling-en Lu, Kimberly Masteller and Michele Valentine, “Creating Spaces for Asian Art: C. T. Loo and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,” Orientations 54, no. 3 (May/June 2023): 88-98.

Oswald Siren, The History of Later Chinese Painting, vol. 1 (London: The Medici Society, 1938), 26 (repro.).

Laurence Sickman, “Notes on Later Chinese Buddhist Art,” Parnassus (April 1939), 12-17, illus (repro.).

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 120, fig. 22 (repro.).

Alexander C. Soper, “Hsiang-Kuo-Ssǔ. An Imperial Temple of Northern Sung,” Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. LXVIII, no. 1 (January – March 1948), 19-45, doi: 10.2307/596233 (repro.).

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 3rd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1949), 157 (repro.).

Julia S. Berrall, “History of Flowers Arrangement,” (London; New York: Studio Publications in association with Crowell, 1953), 106, fig. 129 (repro.).

Aschwin Lippe, Metropolitan Museum of Arts Bulletin, no. 5, Part 1 (New York: May 1965), 32 (repro.).

Aschwin Lippe, “Buddha and the Holy Multitude,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 23, No. 9, Part 1 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, May, 1965), 325-335, pl. 5, http://www,jstor,org/stable/3258142 (repro.).

Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt, “Zhu Haogu Reconsidered: A New Date for the ROM Painting and the Southern Shanxi Buddhist-Daoist,” Artibus Asiae, vol.XLVIII, no. ½ (1987), 12-17, fig. 5 (repro.).

Anning Jing, The Water God’s Temple of the Guangsheng Monastery (Boston, Koln: Brill 2002) (repro.).

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 350, pl. 206 (repro.).

Colin Mackenzie, with contributions by Ling-En Lu, Masterworks of Chinese art: the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, Mo.: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2011), 82, no. 21 (repro.).

Ling-en Lu, “Pigment Style and Workshop Practice in the Yuan Dynasty Wall Paintings from the Lower Guangsheng Monastery” in Original Intentions: Essays on Production, Reproduction, and Interpretation in the Arts of China, edited by Nick Pearce and Jason Steuber (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2012), 74-137, numerous figures (repro.).