Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness

Framed: 81 3/4 × 65 1/2 × 6 inches (207.65 × 166.37 × 15.24 cm)

Exhibition of Works by Holbein and Other Masters of the 16th and 17th Centuries, Royal Academy of Arts, London, December 9, 1950–March 7, 1951, no. 323.

Mostra del Caravaggio e dei Caravaggeschi, Palazzo Reale, Milan, April–June 1951, no. 23.

Anatomy and Art, The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum, Kansas City, MO, May 8–June 5, 1960, no. 54.

‘Masterpieces of Art’: Century Twenty-One Exposition, World’s Fair, Seattle, April 21– September 4, 1962, no. 62.

Art in Italy, 1600-1700, The Detroit Institute of Arts, April 6–May 9, 1965, no. 3.

Caravaggio and His Followers, The Cleveland Museum of Art, October 27, 1971–January 2, 1972, no. 17.

The Age of Caravaggio, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, February 5– April 4, 1985; Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy, May 11–June 30, 1985, no. 85.

Caravaggio and Tanzio: The Theme of St. John the Baptist, The Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, OK, September 17-November 26, 1995; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 13, 1995-February 4, 1996, no. 1.

Caravaggio and His Italian Followers, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT, April 15-July 16, 1998.

Sinners and Saints, Darkness and Light: Caravaggio and his Dutch and Flemish followers, North Carolina Museum of Art, September 27–December 13, 1998; Milwaukee Art Museum, January 29–April 18, 1999; The Dayton Art Institute, May 8 – July 18, 1999, no. 1.

The Genius of Rome, 1592-1623, Royal Academy of Arts, London, January 20- April 16, 2001; Palazzo Venezia, Rome, May–August 2001, no. 112.

Darkness and Light: Caravaggio and His World, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Australia, November 29, 2003-February 22, 2004; National Gallery of Victoria, Australia, March 11-May 30, 2004.

Caravaggio, Scuderie del Quirinale, Rome, February 19-June 13, 2010, unnumbered.

Caravaggio and His Followers in Rome, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, June 17–September 11, 2011; Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, October 16, 2011–January 8, 2012, no. 25.

Bodies and Shadows: Caravaggio and His Legacy, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 11, 2012–February 10, 2013; Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT, March 8–June 16, 2013, no. 4.

Beyond Caravaggio, The National Gallery, London, October 12, 2016 –January 15, 2017, no. 33.

Rivoluzione Caravaggio, Museum Barberini, Potsdam, Germany, March 6-July 7, 2025.

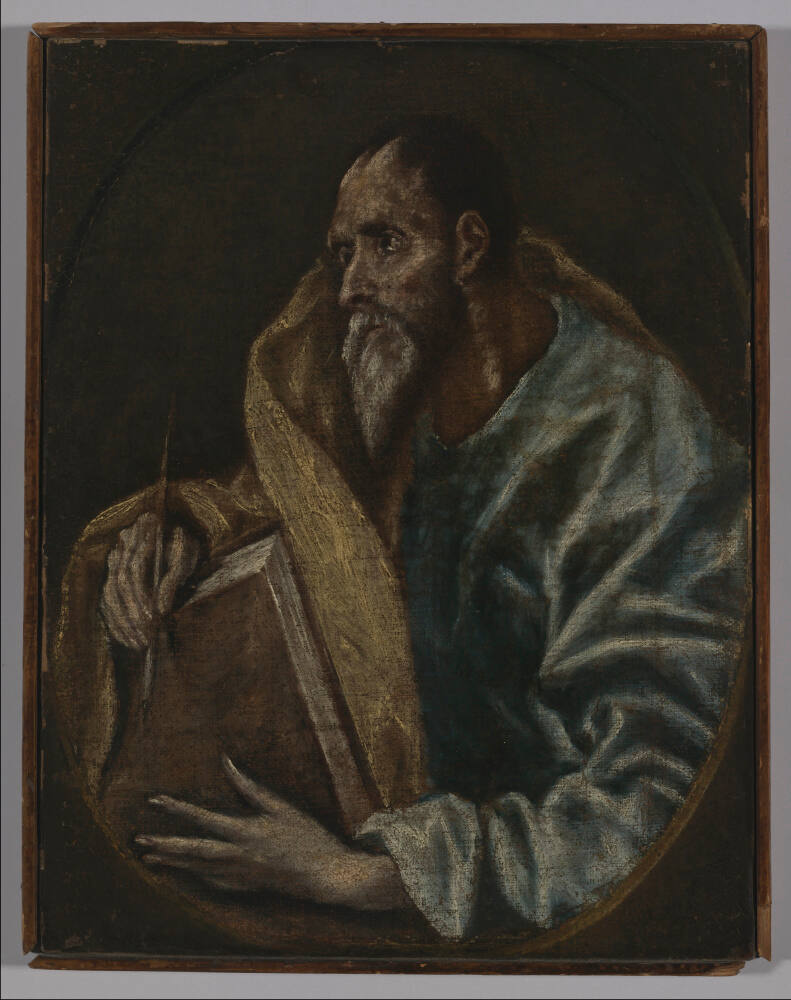

This masterpiece, one of the Museum's greatest treasures, is one of only a few original works by Caravaggio in American collections. Although he never accepted pupils, Caravaggio's enormous influence on other artists played a vital role in the development of the Italian Baroque. In this Saint John the Baptist, Caravaggio has traded idealism for what oftentimes became in his own time a controversial realism. He has literally stripped the Baptist of nearly all traditional attributes (halo, lamb and banderole inscribed Ecce Agnus Dei or Behold the Lamb of God) leaving the brooding intensity of the saint's emotional state as the subject of the painting. Saint John's solemn pensiveness is reinforced by a Caravaggio trademark: the dramatic contrast of deep, opaque shadows, playing across his body and shrouding the sockets of his eyes, with a bright light that illuminates the Baptist from above and to his right. This stark contrast of light and darkness, the brilliant scarlet of the saint's cloak and Caravaggio's placement of him in the foreground, close to our own space, all contribute to the dramatic impact of the painting. Evidence of Caravaggio's working method, in which he incised lines into the gesso ground to guide his hand while painting, can be easily seen along the sitter's left leg in the right corner. Caravaggio most likely borrowed the Baptist's pose from one of Michelangelo's seated prophets and sibyls on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, Rome.

Caravaggio's Saint John the Baptist was commissioned by a Roman banker, Ottavio Costa, for a small, private chapel on his estate near Genoa. The saint’s brooding melancholy surely inspired silence and introspection in those who visited the chapel, an effect recorded in a guidebook of 1624:

“Before ascending to the…church,

in the narrow but fruitful valley, one comes upon a small, holy oratory…formerly

the parish church, restored in the modern style in honor of that mysterious

nightingale who announces the coming of Christ, St. John the Baptist. The image of him in the desert, mourning

human miseries, was painted by the famous Michelangelo Caravaggio, and it moves

not only the brothers but also visitors to penitence.”

Commissioned from the artist by Ottavio Costa (1554-1639), Rome, 1605-1639 [1];

By descent to his son, Benedetto Costa (1603-1659), Rome, 1639-1659;

Inherited by his wife, Maria Costa Cattaneo, Rome, 1659;

By descent to her daughter, Clelia Del Palagio Costa (1641-1719), Rome, by 1719;

By descent to her son, Guido Del Palagio (d. 1732), Rome, 1719-1732;

By descent to his niece, Maria Origo Del Palagio (d. 1770), Rome, 1732-1770 [2];

By descent to her son, Carlo Origo (d. 1792), Rome, 1770-1792;

Inherited by his brother, Vincenzo Origo (d. 1808), Rome, 1792-1808;

By descent to his son, Giuseppe Origo (d. 1833), Rome, 1808-1833 [3];

Bequeathed to the Congregation of the Works of the Divine Pietà, Rome, 1833-1854 [4];

Purchased from the Congregation of the Works of the Divine Pietà, Rome, by Antonio Del Cinque, Rome, 1854-at the latest 1857;

Galleria del Sacro Monte di Pietà, Rome, by 1857-December 28, 1875 [5];

Its sale, Quadri, sculture in marmo, musaici, pietre colorate, bronzi ed altri oggetti di Belle Arti esistenti nella Galleria già del Monte di Pietà di Roma, ora della Cassa dei Depositi e Prestiti, Rome, December 28, 1875, lot 1175 [6];

Rosina, Lady Clifford Constable (née Brandon, ca. 1831-1908), Rome, by 1908 [7];

Inherited by her step-grandnephew, Lt. Col. Walter George Raleigh Chichester Constable (1863-1942), Burton Constable, Yorkshire, 1908-1942 [8];

By descent to his son, Brigadier Raleigh Charles Joseph Chichester Constable (1890-1963), Burton Constable, Yorkshire, 1942-January 15, 1951;

Purchased from Chichester Constable by Edward Speelman and Sons, London, stock no. 31351, January 15, 1951 [9];

With Thomas Agnew and Sons, London, Picture stock book 12, no. J.0426, on joint account with Edward Speelman and Sons, London, Vitale Bloch, and Volterra, January 15, 1951-1952 [10];

Purchased from Thomas Agnew and Sons by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1952.

NOTES:

[1] The painting is included in Ottavio Costa’s will, dated January 18-24, 1639, as E più un altro quadro con l’imagine di S. Gio. Batta nel diserto fatto dall’ istesso Caravaggio, Archivio Storico Capitolino, Rome, Notai dell’ A.C., Hadrianus Gallus, sez. XLII, Strumenti 1639, unpaginated entry at beginning of volume; published in L. Spezzaferro, “Detroit’s ‘Conversion of the Magdalene’, The Documentary Findings: Ottavio Costa as a Patron of Caravaggio,” Burlington Magazine vol. 116 (1974): 584, n. 36. For more on the early provenance of the painting and the Ottavio Costa patrimony, see Maria Cristina Terzaghi, Caravaggio, Annibale Carracci, Guido Reni: tra le Ricevute del Banco Herrera & Costa Rome: “L’Erma” di Bretschneider, 2007 and Josepha Costa Restagno, Ottavio Costa (1554-1639): le sue case e i suoi quadri, Bordighera-Albenga: Istituto Internazionale di Studi Liguri, 2004.

[2] The painting is listed as no. 32, Un quadro di 7, e 5 con cornice/liscia dorata rappresentante San Giovanni originale del Caravaggi, in an inventory of Guido Del Palagio’s collection dated May 30, 1732, published in Restagno, 108.

[3] The painting is listed as no. 97, Un quadro grande per alto, rappresentante San Giovanni Battista, dipinto/in tela di Michel Angelo da Caravaggio, con cornice dorata, in an inventory of Giuseppe Origo’s collection dated January 15-17, 1834, published in Restagno, 113.

[4] According to Restagno, 66, Giuseppe Origo’s will granted his wife usufruct of the painting until the time of her remarriage, which occurred sometime between 1834 and 1844, at which point it was transferred to the Congregation of the Works of the Divine Pietà and installed in the home of one of its members, Alessandro Poncini. It was transferred again to another member’s home, Marco Santelli, on March 20, 1844. The painting was offered for sale by the Congregation of the Works of the Divine Pietà at Quadri e rami antichi di varj autori, March 26, 1846, lot 23, as S. Gio. Battista figura grande al vero, originale del Caravaggio, but failed to sell. See Restagno, 124. See also Terzaghi, 296-297, n. 94.

[5] The painting is listed as no. 83 in an 1857 inventory of the Galleria del Sacro Monte di Pietà collections: Catalogo de quadri, sculture in marmot, musaici, pietre colorate, bronzi ed altri oggetti di Belle Arti esistenti nella Galleria del Sagro Monte di Pietà di Roma (Rome, 1857): 6. See Restagno 2004, p. 68, n. 223. The Sacro Monte di Pietà was a bank that granted no-interest loans in exchange for a pledge object.

[6] According to Restagno, 68, the painting may have been sold, along with other works from the Ottavio Costa patrimony, in order to pay the money still owed to the Congregation of the Divine Pietà for their purchase in 1854.

[7] According to David Connell, Director, Burton Constable Foundation, in emails to MacKenzie Mallon, Specialist, Provenance, August 5-6, 2015: following the death of Rosina’s husband, Sir Thomas Aston Clifford Constable (1806-1870), Rosina removed a number of paintings from Burton Constable and took them with her to several subsequent residences (she was married again and widowed twice), including Dunbar House, Teddington; Haywood Abbey, Staffordshire; 36 Avenue du Bois de Boulogne, Paris; Bolney Grange, Hayward’s Heath and finally Palazzo Barachini, 8 Via Venti Settembre, Rome, after 1880. Her Rome address is not listed in a description of her residences in a 1901 peerage. Therefore, she may have arrived in Rome after 1901. An inventory of Rosina’s paintings during her time at Dunbar House (Burton Constable Archive, Yorkshire) does not include the Caravaggio. The collection was inventoried again in Rome at the time of Rosina’s death in 1908 in the Official Inventory and Valuation of the Effects at No. 8 Via Venti Settembre, Rome, The Estate of Late Lady Constable, 1908, Burton Constable Archive, Yorkshire. Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness is included in this 1908 list as: “No. 2 Gallery, no. 50: Large carved and gilt frame with oil painting of shepherd signed Garenaggio [sic].” Therefore, it is possible Rosina acquired the painting during her time in Rome, sometime after 1901-1908. Pursuant to her will, the painting was returned to Burton Constable in 1910 with the rest of the collection.

[8] According to Connell (see note 8), the painting appears again in a 1910 inventory of the Chichester Constable collection, conducted for insurance purposes by Waring & Gillow Ltd., in which it is documented on page 197 as in the staircase: Full-length figure of St. John the Baptist, by Caravaggio – 5 ft 9 in by 4 ft 3 in gilt frame, Burton Constable Archive, Yorkshire; and again in a 1924 list of paintings and prints at Burton Constable as no. 110, St. John the Baptist Caravaggio, Staircase Hall, Burton Constable Archive, Yorkshire.

[9] According to Anthony Speelman, in a telephone call with MacKenzie Mallon, Specialist, Provenance, May 17, 2016.

[10] Thomas Agnew and Sons, Vitale Bloch and Volterra each

acquired a one-quarter share of the painting’s ownership from Edward Speelman

and Sons on January 15, 1951. The National Gallery Research Centre, London,

Thomas Agnew and Sons Archive, Picture stock book 12, reference NGA27/1/1/14,

Trade X Day Book 20, NGA27/13/1/20, January 15, 1951, Ledger reference F.546,

and Trade X Day Book 21, NGA27/13/1/21, August 8, 1952, Ledger references

F.334, F.777 and F.546.

Roberto Longhi, “Ultimi studi sul Caravaggio e la sua cerchia,” Proporzioni 1 (1943): 15.

Lasarte J. Ainaud, “Ribalta y Caravaggio,” Anales y Boletin de los Museos de Arte de Barcelona 3 (1947): 388-89.

Ellis K. Waterhouse, The Getty Center, Los Angeles, Resource Collections of The Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, Waterhouse-house Notebook no. 34, 1948, p. 148.

Catalogue of the Exhibition of Works by Holbein and Other Masters of the 16th and 17th Centuries, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1950), 130, (repro.).

Mostra del Caravaggio e dei Caravaggeschi, exh. cat. (Milan: Palazzo Reale, 1951), 7, 24, (repro.).

Edoardo Arslan, “Appunto su Caravaggio,” Aut Aut, no. 5 (1951): 446.

G. Castelfranco, “Mostra del Caravaggio,” Bollettino d’Arte 36 (1951): 285.

Roberto Longhi, “Sui margini caravaggeschi,” Paragone 2, no. 21 (1951): 30.

Denis Mahon, “Egregius in Urbe Pictor: Caravaggio Revised,” The Burlington Magazine 93 (1951): 234.

Bernard Berenson, Del Caravaggio: Delle sue incongruenze e della sua fama (Florence: Electa, 1951), 33, 46.

Marco Valesecchi, Caravaggio (Milano: Electa, 1951), 53, (repro.).

Lionello Venturi, Il Caravaggio (Novara: Istituto Geografico de Agostini, 1951), 41n35.

Denis Mahon, “Addenda to Caravaggio,” The Burlington Magazine 94 (1952): 19.

Roberto Longhi, Il Caravaggio (Florence: Fondazione di studi di storia dell’arte, 1952), 32-33, (repro.).

W. Shield, “Acquisition at Nelson Gallery Called One of Best in 20 years,” Kansas City Times (January 30, 1953): 44, (repro.).

“Enriching U.S. Museums … Kansas City,” Art News 51 (February 11, 1953): 51 (repro.).

Denis Mahon, “The Literature of Art: Contrasts in Art-Historical Method: Two Recent Approaches to Caravaggio,” The Burlington Magazine 95 (1953): 213, 213n9.

Bernardo Berenson, Caravaggio: His Incongruity and His Fame (London: Chapman and Hall, 1953), 32, 62, (repro.).

Roger P. Hinks, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio: His Life, His Legend, His Works (London: Faber and Faber, 1953), no. 73, pp. 71-72, 110, (repro.).

H. Swarzenski, “Caravaggio and Still-Life Painting,” Bulletin of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts 52, no. 287 (1954): 35, (repro.).

J.E. Hicks, “Social Realism Is Found in Paintings by Caravaggio, Once Thought Shocking,” Kansas City Times (September 12, 1955): 28, (repro.).

Eugenio Battisti, “Alcuni Documenti su Opere del Caravaggio,” Commentari 6 (1955): 183n31.

Fritz Baumgart, Caravaggio: Kunst und Wirklichkeit (Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1955), 33, 101 (repro.).

Walter F. Friedlaender, Caravaggio Studies (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955), 171-72, (repro.).

“A Major Work by Caravaggio is Identified,” The New York Times (July 2, 1956): unapaginated.

Roberto Longhi, Il Caravaggio (Milan: Aldo Martello, 1957), 20, 36, (repro.).

Hugo Wagner, Michelangelo da Caravaggio (Bern: Eicher, 1958), 106-109, 207n439, (repro.).

Andre Berne-Joffroy, Le Dossier Caravage (Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1959), 260, 332, 339, 374, (repro.).

Paola Della Pergola, Galleria Borghese: I Dipinti, vol. 2 (Rome: Istituto Poligrafico Dello Stato Libreria Dello Stato, 1959), 79, (repro.).

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 71, 262, (repro.).

Anthony M. Clark, “A Late, Great Guido Reni,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 54 (April 1960): 3.

“Anatomy and Art: May 8 to June 5, 1960,” Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum Bulletin 3 (May 1960): 20 (repro.).

Roberto Longhi, “Un Originale del Caravaggio a Rouen e il problema delle copie caravaggesche,” Paragone 11, no. 21 (1960): 34 (repro.).

René Jullian, Caravage (Paris: Editions IAC, 1961), 149n.69, 151-53, 228, (repro.).

William R. Graves, “The Nelson Gallery to the Seattle Fair,” The Kansas City Star (August 19, 1962): 10D, (repro.).

Silvio Toree, “Abbiamo trovato un quadro: E un Caravaggio?,” I’l Giornale d’Italia 62, nos. 9-10 (1962): 9 (repro.).

Constantino Baroni, ed., All the Paintings of Caravaggio (London: Oldbourne, 1962), 23 (repro.).

Angela Ottino Della Chiesa, Caravaggio (Bergamo: Istituto Italiano d’Arte Grafische, 1962), 55.

Raffaelo Causa, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, vol. 2 (Milan: Fratelli Fabbri, 1963), 155.

Lionello Venturi, Il Caravaggio, 2nd ed. (1951; Novara: Istituto Geografico De Agostini, 1963), 43n35.

Francis H. Dowley, “Art in Italy, 1600 to 1700 at Detroit Institute of Arts,” Art Quarterly 27 (1964): 520.

Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez, “Dos importantes pinturas del Barroco,” Archivo Espanol del Arte 37 (1964): 14.

Giuseppe Delogu, Caravaggio (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1964), (repro.).

Caterina Marcenaro, Dipinti Genovesi del XVII e XVIII Secolo (Torino: ERI-Edizioni RAI Radioteleveisione Italiana, 1964), unpaginated.

Bruno Molajoli, Notizie su Capodimonte: Catalogo delle Gallerie e del Museo (Naples: L’arte Tipografica, 1964), 52.

Art in Italy 1600-1700, exh. cat. (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 1965), 16-17, 25, 16, (repro.).

Sylvie Beguin, Le Caravage et la peinture italienne du XVIIe siècle, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée du Louvre, 1965), 57.

D. Posner, “The Baroque Revolution in Italy,” Art News 64 (April 1965): 32, 57.

Howard Hibbard and Milton Lewine, “Seicento at Detroit,” The Burlington Magazine 107 (1965): 370.

Denis Mahon, “Stock-taking in Seicento Studies,” Apollo 82 (1965): 385n17.

R.T. Coe, “Letters to the Editors,” Art Quarterly 29 (1966): 103.

Gus Baker and Paul H. Reno, Paintings by the Masters: A Treasury of Famous Paintings (Fort Lauderdale, 1966), 13 (repro).

Andre Chastel and Angela Ottino della Chiesa, Tout l’oeuvre peint du Caravage (Paris: Flammarion, 1967), no. 41, p. 95, (repro).

Renato Guttuso and Angela Ottino Della Chiesa, L’opera complete del Caravaggio (Milan: Rizzoli, 1967), no. 55, p. 98, (repro).

Alfred Moir, The Italian followers of Caravaggio (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967), 1: 256n2; 2: 57.

Roberto Longhi, Caravaggio (Leipzig: Edition Leipzig, 1968), 32, (repro.).

“Family heirloom was sold to American art gallery,” Art and Antiques Weekly (May 3, 1969): unpaginated.

Michael Kitson, The Complete Paintings of Caravaggio (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1969), no. 53, p. 98, (repro.).

Patrick Matthiesen and Stephen Pepper, “Guido Reni: An Early Masterpiece Discovered in Liguria,” Apollo 91 (1970): 456.

Richard E. Spear, Caravaggio and His Followers, exh. cat. (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1971), 11, 61, 75-76, (repro.).

Richard E. Spear, Caravaggio and His Followers, 2nd ed., exh. cat. (1971; New York: Harper and Row, 1975), 11, 61, 75-76.

Ralph Fabri, “Caravaggio and His Followers,” Today’s Art (December 1971): (repro).

R. Ward Bissell, “Orazio Gentileschi: Baroque without rhetoric,” Art Quarterly 34 (1971): 285-86, (repro.).

Mia Cinotti and Gian Alberto Dell’Acqua, Il Caravaggio e le sue grandi opera da San Luigi deii Francesi (Milan: Rizzoli, 1971), 128, 195n447.

Julius S. Held, “Caravaggio and His Followers,” Art in America 60 (May-June 1972): 42.

Evelina Borea, “Considerazioni sulla Mostra ‘Caravaggio e I suoi seguaci’ a Cleveland,” Bolletino d’Arte 57 (1972): 154.

Ralph T. Coe,

“The Baroque and Rococo in France and Italy,” Apollo 16 (1972): 530-32, (repro.) [repr. in Denys Sutton, ed., William Rockhill Nelson Gallery, Atkins

Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City (London: Apollo Magazine, 1972), 62,

(repro.)].

Benedict Nicolson, “Current and Forthcoming Exhibitions: Caravaggesques at Cleveland,” The Burlington Magazine 114 (1972): 113.

D. Stephen Pepper, “Caravaggio riveduto e corretto: La mostra di Cleveland,” Arte Illustrata 5 (1972): 170, 172, (repro.).

Carlo Volpe, “Annotazioni sulla mostra caravaggesca di Cleveland,” Paragone 23, no. 263 (1972): 58, (repro.).

A. Werner, “Ausstellunge…USA, The Cleveland Museum of Art, Exhibition: Caravaggio and His Followers,” Pantheon 30 (1972): 70.

Cesare Brandi, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (Rome, 1972), 109.

Burton Fredericksen and Federico Zeri, Census of Pre-Nineteenth-Century Italian Paintings in North American Public Collections (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1972), 44, 417, 589.

Carlo Volpe, “Una proposta per Giovanni Battista Crescenzi,” Paragone, no. 275 (1973): 30.

Mia Cinotti and Francesco Rossi, Immagine del Caravaggio (Milan: Pizzi, 1973), 87-88, 188, (repro.).

Frederick J. Cummings, Notes on Caravaggio’s ‘The Conversion of the Magdalene (Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 1973), 11, 12, 15.

Valerio Mariani, Caravaggio (Rome: Istituto poligrafico dello Stato Libreria, 1973), 130.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 109, 109, (repro.).

James L. Greaves and Meryl Johnson, “Detroit's 'Conversation of the Magdalen' (The Alzaga Caravaggio): New Findings on Caravaggio's Technique in the Detroit Magdalen,” special issue, The Burlington Magazine 116, no. 859 (October 1974): 567n6, 568.

Luigi Spezzaferro, “Detroit's 'Conversation of the Magdalen' (The Alzaga Caravaggio): The Documentary Findings: Ottavio Costa as a Patron of Caravaggio,” special issue, The Burlington Magazine 116, no. 859 (October 1974): 584n36, 585, 586.

Luigi Dania, “A ‘St. John the Baptist’ by Valentin,” The Burlington Magazine 116 (1974): 619n2.

B. Nicolson, “Editorial: Caravaggio and His Circle in the British Isles,” The Burlington Magazine 116 (1974): 559.

Arturo Bovi, Caravaggio (Florence: d’arte Il Fiorino, 1974), 16, 30, 242, 243, (repro.).

Maurizio Marini, Io Michelangelo da Caravaggio (Rome: Studio B di Bestetti e Bozzi, 1974), 160, 161, 386-87, 460, 468, (repro.).

John Walker, Self-Portrait with Donors: Confessions of an Art Collector (Boston: Little, Brown, 1974), 34, (repro.).

Mia Cinotti, ed., Novita sul Caravaggio: Saggi e contribute (Milan, 1975), 30, 112n39, 117-118, (repro.).

Svetlana Nikolaevna Vsovolozhskaya and Irina Vladimirovna Linnik, Paintings in Soviet Museums: Caravaggio and His Followers (St. Petersburg: Aurora Art, 1975), unpaginated, (repro.).

Alfred Moir, Caravaggio and His Copyists (New York: New York University Press, 1976), 13, 66, 97, (repro.).

Laura Magnani, “Due Culture nell’entoroterra di Albenga,” Indice per I Beni Culturali del Territorio Ligure 2 (March-April 1977): 28-29.

Gian Lorenzo Mellini, “Momenti del Barocco: Lanfranco e Caravaggio,” Comunita 31 (1977): 392n6.

Roberto Longhi, Caravaggio, 2nd ed. (Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1977), 29.

M. Wakakuwa, L’art du monde: Caravaggio (Tokyo, 1978), 119-120.

Benedict Nicolson, The International Caravaggesque Movement (Oxford: Phaidon, 1979), 33.

John Gash, Caravaggio (London: Jupiter, 1980), 14, 92, (repro.).

Maurizio Marini, Caravaggio: Werkverzeichnis (Frankfurt: Ullstein, 1980), no. 36, p. 36, (repro.).

Maurizio Marini, “Gli esordi del Caravaggio e il concetto di ‘natura’ nei primi decenni del seicento a Roma: Equivoci del caravaggiomo,” Artibus et Historiae 2, no. 4 (1981): 46n14 (repro.).

R. Ward Bissell, Orazio Gentileschi and the poetic tradition in Caravaggesque painting (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1981), 15, (repro.).

Christopher Wright, Italian, French and Spanish Paintings of the Seventeenth Century (London: Frederick Warne, 1981), 2.

F. Zeri, ed., Storia dell’arte italiana: Parte seconda; Dal Medioevo al Novecento, II. Dal conquento all’ottocento, I. Cinquento e Seicento (Turin: Einaudi, 1981), 356n1.

Il Museo Diocesano di Albenga, (Bordighera: Istituto Internazionale Di Studi Liguri, 1982), 79, (repro.).

Alfred Moir, Caravaggio (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1982), 19, 50, 124, 134, (repro.).

Maurizio Marini, “Equivoci del caravaggismo 2: A) Appunti sulla tecnica del ‘naturalism’ seicentesco, tra Caravaggio e Manfrediana ‘methodus’; B) Caravaggio e I suoi ‘doppi’; il problema delle possibili collaborazioni,” Artibus et Historiae 4, no. 8 (1983): 132, (repro.).

Mia Cinotti and Gian Alberto Dell’Acqua, I pittori bergamachi: Il seicento, vol. 1, Michelangelo Merisi detto il Caravaggio: Tutte le opere (Bergamo: Poligrafiche Bolis, 1983), no. 21, pp. 225, 418, 443-44, (repro.).

John E. Gedo, Portraits of the Artists: Psychoanalysis of Creativity and its Vicissitudes (New York: Guilford Press, 1983), 167, (repro.).

Howard Hibbard, Caravaggio, (New York: Harper & Row, 1983), 191-93, 319-20, (repro.).

Giorgio Bonsanti, Caravaggio (Milan: Scala, 1984), 60, (repro.).

Mina Gregori, Luigi Salerno, and Richard E. Spear, The Age of Caravaggio, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985), 163, 224, 225, 257, 265, 298, 300-303, 310, 312, (repro).

William B. Jordan, Spanish still life in the golden age, 1600-1650, exh. cat. (Forth Worth: Kimbell Art Museum, 1985), 155, (repro.).

Dale Harris, “Rebel with a cause: Caravaggio defied the conventions of life and art,” Connoisseur 215 (February 1985): 54.

Giovanni Previtali, “Libri e mostre: Caravaggio e il suo tempo,” Prospettiva 41 (April 1985): 79n16, (repro.).

Maurizio Calvesi, “Le realta del Caravaggio,” Storia dell’arte 55 (1985): 277, (repro.).

C. Puglisi, “Ausstellungen: The Age of Caravaggio,” Kunstchronik 38 (1985): 449.

John T. Spike, “Letter from New York: The Age of Caravaggio,” Apollo 121 (1985): 417.

Carel van Tuyll, “Exhibition Reviews. New York and Naples: Caravaggio,” The Burlington Magazine 126 (1985): 487, (repro.).

Dante Bernini et al., Caravaggio nei Musei romani, exh. cat. (Rome: Palombi, 1986), 35.

Keith Christiansen, “Caravaggio and ‘L’esempio davanti del natural,” Art Bulletin 68, no. 3 (September 1986): 424-25, 434, 437-440, 442, 445, (repro.).

Derek Jarman, Derek Jarman’s “Caravaggio”: The Complete Film Script and Commentaries (London: Thames and Hudson, 1986), 80, (repro.).

Edward J. Sullivan, Catalogue of Spanish Paintings (Raleigh: North Carolina Museum of Art, 1986), 75, (repro.).

Fernando Bologna, “Alla ricerca del vero San Francesco in estasi di Michel Agnolo da Caravaggio per il cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte,” Artibus et Historiae 8, no. 16 (1987): 162 (repro.) [repr. in Ferdinando Bologna, L’incredulita del Caravaggio e l’esperienza delle “cose naturali” (Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 1992), 215, 241].

Maurizio Calvesi, ed., L’ultimo Caravaggio e la cultura artistica a Napoli, in Sicilia, e a Malta (Syracuse: Ediprint 1987), 108, 118, 120, (repro).

Gian Vittorio Castelnovi, Dal seicento al primo novecento, vol. 2, La prima metà del seicento; Dall’ Ansaldo a Orazio de’Ferrari (Genoa: Sagep, 1987), 150.

Diane Loupe, “Nelson curator hunts for historical, aesthetic match of art and environment,” The Kansas City Star (1987): 1C, 4C.

Bartolomeo Manfredi and Arnauld Brejon de Lavergnee, Dopo Caravaggio: Bartolomeo Manfredi e la Manfrediana Methodus, exh. cat. (Milan: A. Mondadori, 1987), 53-55, (repro.).

Maurizio Marini, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio “pictor praestantissimus” (Rome: Newton Compton, 1987), 212-13, 468-69, 488, 556, (repro.).

Joseph J. Rishel, The Henry P. McIlhenny Collection: An Illustrated History (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1987), 109.

Keith Christiansen, “Appendix: Technical Report on ‘The Cardsharps,’” The Burlington Magazine 130 (1988): 26n2.

Andre Chastel and Angela Ottino della Chiesa, Tout l’oeuvre peint du Caravage, 2nd ed. (Paris: Flammarion, 1988), 95, (repro.).

Anna Maria Giusti, Empoli: Museo della Collegiata, Chiese di Sant’ Andrea e S. Stefano (Bologna: Calderini, 1988), 92.

E. Goheen, The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1988), 52, 53, (repro.).

Antonio Rotundo, ed., Tutto Caravaggio a Roma (Rome: Rotundo, 1988), 27, 108.

Mina Gregori, “Il Sacrificio di Isacco: Un inedito e considerazioni su una fase savoldesca del Caravaggio,” Artibus et historiae 10, no. 20 (1989): 116, 120, (repro.).

D.Stephen Pepper, Guido Reni, 1575-1642, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1989), 170.

Robert S. Cauthorn, “Light gives new life to a familiar work, Caravaggio seen as never before,” The Kansas City Star (April 1, 1990): J1, J8, (repro.).

C.E. Gilbert, “Add one Caravaggio,” New Criterion 8 (May 1990): 59.

Maurizio Calvesi, Le realtà del Caravaggio (Turin: G. Einaudi, 1990), 243, 424.

Benedict Nicolson, Caravaggism in Europe, 2nd ed., rev. by L. Vertova (Turin: Allemandi, 1990), 81, (repro.).

Roger Ward, “Selected Acquisitions of European and American Paintings at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, 1986-1990,” The Burlington Magazine (1991): 156.

Mia Cinotti, Caravaggio: La vita e l’opera (Bergamo: Edizioni Bolis, 1991), 119-120, 212, (repro.).

Margrit Franziska Brehm, Der Fall Caravaggio: eine Rezeptionsgeschichte (Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang, 1992), 419.

Ezia Gavazza and Giovanna Rotondi Termineillo, eds., Genova nell’età barocca, exh, cat. (Bologna: Nuova Alfa, 1992), 73n16, 76, 108-10, 247.

Nicholas H.J. Hall, ed., Colnaghi in America: A survey to commemorate the first decade of Colnaghi New York (New York: Colnaghi, 1992), 31.

Sebastian Schutze and Thomas Willette, Massimo Stanzione: L’opera complete (Napoli: Electa, 1992), 195.

Michael Churchman and Scott Erbes, High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1933-1993 (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 64, (repro.).

Michael Hilaire and Patrick Ramade, eds., Century of Splendor: Seventeenth-Century Painting in French Private Collections, exh, cat. (Montreal, Canada: The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 1993), 89, (repro.).

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 33, 129, 160, (repro.).

Chiyo Ishikawa et. al., A Gift to America: Masterpieces of European Painting from the Samuel H. Kress Collection, exh. cat. (New York: Abrams, 1994), 52-53, (repro.).

Jed Jackson, Art: A Comparative Study (Dubuque: Kendall/Hunt Publishing, 1994), 14-15, (repro.).

Thomas Buser, Experiencing Art Around Us (Minneapolis/St. Paul: West Publishing, 1995), 480-481, (repro.).

Richard P. Townsend and Roger Ward, Caravaggio and Tanzio: The Theme of St. John the Baptist, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: The Nelson Gallery Foundation, 1995), v-vi, 6-13, 16-17, 21, 31-32, 38-40, 46-48, (repro.).

Elliot W. Rowlands, The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Italian Paintings, 1300-1800 (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1996), 19-21, 212-226, (repro.).

Dennis P. Weller, Sinners and saints, darkness and light: Caravaggio and his Dutch and Flemish followers, exh. cat. (Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina Museum of Art, 1998), 32, 51, 58, 59, 60, 153, 161, 205, (repro.).

“Together again, artfully,” Sunday Telegraph (May 17, 1998): unpaginated.

Michael Kimmelman, “In Connecticut, Where Caravaggio First Landed,” The New York Times (July 17, 1998).

“Masters of Light and Dark,” Southern Living (September 1998): NC22, NC24, (repro.).

Owen McNally, “Caravaggio and his Italian Followers,” Art News 97 (September 1998).

“Sinner or saint? Caravaggio’s paintings feature working-class people posing as biblical figures and saints,” Meridian (September 1998): 8, (repro.).

Richard P. Townsend, “Caravaggio and his followers,” Apollo 148, no. 438 (September 1998): 49.

Kate Dobbs Ariail, “Saints, sinners and spirits are all the rage this fall,” Independent Weekly 8 (September 2-8, 1998): 19, (repro.).

Kathy Whyde Jesse, “Mélange of Art: Area explores everything from Sinners to patrimony to jazz,” Dayton Daily News (September 20, 1998).

Chuck Twardy, “Enduring Light: His life was short and troubled, but Caravaggio’s influence reached far afield,” The News and Observer (September 27, 1998): G1, (repro.).

Michele Natale, “More Darkness than Light: A single Caravaggio headlines NCMA’s latest exhibit,” Spectator (September 30, 1998): unpaginated, (repro.).

“17th-century biblical art on display,” Going on Faith Magazine (October/November 1998): 12.

Tom Patterson, “Sinners and Saints,” Winston-Salem Journal (October 4, 1998): E1, E7, (repro.).

Jane Grau, “Caravaggio! N.C. Museum of Art showcases the movement that out flesh and blood on canvas,” The Charlotte Observer (October 25, 1998): F1, (repro.).

Julie Cole, “At the Museum: A Natural Leader,” Southern Accents 21, no. 6 (November/December 1998): 80, (repro.).

Helen Langdon, Caravaggio: A Life (London: Random House, 1998), 308, (repro.).

“Caravaggio Masterpiece arrives,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel (January 26, 1999): (repro.).

Giovanni Romano, ed., Percorsi caravaggeschi tra Roma e Piemonte (Torino, Fondazione C.R.T., Cassa di Risparmio di Torino, 1999), 91, (repro.).

Antonio Vannugli, “Enigmi Caravaggeschi: I quadri di Ottavio Costa,” Storia dell’Arte 99 (May-August 2000): 57, 59, 63-64 (repro.).

Bert Treffers, Caravaggio nel sangue del Battista (Rome: Associazione Culturale Shakespeare and Company 2, 2000), 38, (repro.).

Beverly Louise Brown, ed., The Genius of Rome 1592-1623, exh. cat (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2001), 299, 300, (repro.).

John Nolan, John the Baptist and the Baroque vision, exh. cat. (Greenville, S.C.: Bob Jones University Museum and Gallery, 2001), 44, 46, (repro.).

Theodore K. Rabb, “When Baroque Passion Ignited Renaissance Cool,” The New York Times (April 1, 2001): AR39, (repro.).

Conrad Rudolph and Steven F. Osrow, “Isaac Laughing: Caravaggio, non-traditional imagery and traditional identification,” Art History 24, no. 5 (November 2001): 665, 666, (repro.).

Véronique Damian, Deux caravagesques lombards à Rome et quelques récentes acquisitions (Paris: Galerie Canesso, 2001), 18, 60, 61, 62, (repro.).

John T. Spike, Caravaggio (New York: Abbeville Press, 2001), 158, 165, (repro.).

Troy Melhus, “Kansas City and highbrow art? Jazzy town corrals rich lineup of museums, galleries,” Minneapolis Star Tribune (May 5, 2002): unpaginated.

Josepha Costa Restagno, Ottavio Costa (1554-1639): le sue case e i suoi quadri: ricerche d'archivio (Genoa: Istituto internazionale di studi liguri, 2004), 63-69, 78, (repro.).

Maurizio Marini, Caravaggio "pictor praestantissimus": l'iter artistico completo di uno dei massimi rivoluzionari dell'arte di tutti i tempi, 3rd ed. (Rome: Newton Compton, 2005), 254, 255, 484, 485, (repro.).

John T. Spike, “Caravaggio Interpreted like a camera, centuries before its invention,” Art & Antiques (November 2007): 192, (repro.).

Maria Cristina Terzaghi, Caravaggio, Annibale Carraci, Guido Reni: Tra le Ricevute del Banco Herrera & Costa (Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider, 2007), 295- 300, 330, 374, 382, 386, 444, (repro.).

Sebastian Schütze, Caravaggio: The Complete Works (Köln: Taschen, 2009), no. 35, pp. 122, 267, 268, (repro.).

Lucy Gordan, “The Genius of Caravaggio: The Father of Modern Painting,” Inside the Vatican (April 2010): 85, (repro.).

Claudio Strinati, Caravaggio, exh. cat. (Milan: Skira, 2010), 152-157, (repro.).

Rosella

Vodret, Caravaggio: The Complete Works

(Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2010), no. 36, pp. 17, 26, 92, 138-139, 140,

(repro.).

David Franklin and Sebastian Schütze, Caravaggio and Followers in Rome, exh.cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 212, 214,242, (repro.).

J. Patrice Marandel, ed., Caravaggio and His Legacy, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 2012), 41, 155, (repro.).

Andrew Berardini, “Caravaggio’s John the Baptist in the Wilderness,” ARTslant, November 12, 2012, accessed December 5, 2012, http://www.artslant.com/la/articles/show/32772.

Gert Jan van der Sman, ed., Caravaggio and the Painters of the North, exh. cat. (Madrid : Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, 2016), 80-81, (repro.).

Letizia Treves, Beyond Caravaggio, exh. cat. (London: The National Gallery, 2016), 17, 26-27, 29n39, 130-132, 186, (repro.).

Rosella Vodret, ed., Caravaggio: Works in Rome: Technique and Style, vol. 2, Essays (Milano: Silvana, 2016), 272-273, 522-523, 526-527, 681.

Julian Zugazagoitia and Laura Spencer. Director's Highlights: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Celebrating 90 Years, ed. Kaitlyn Bunch (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), 60-61, (repro.).