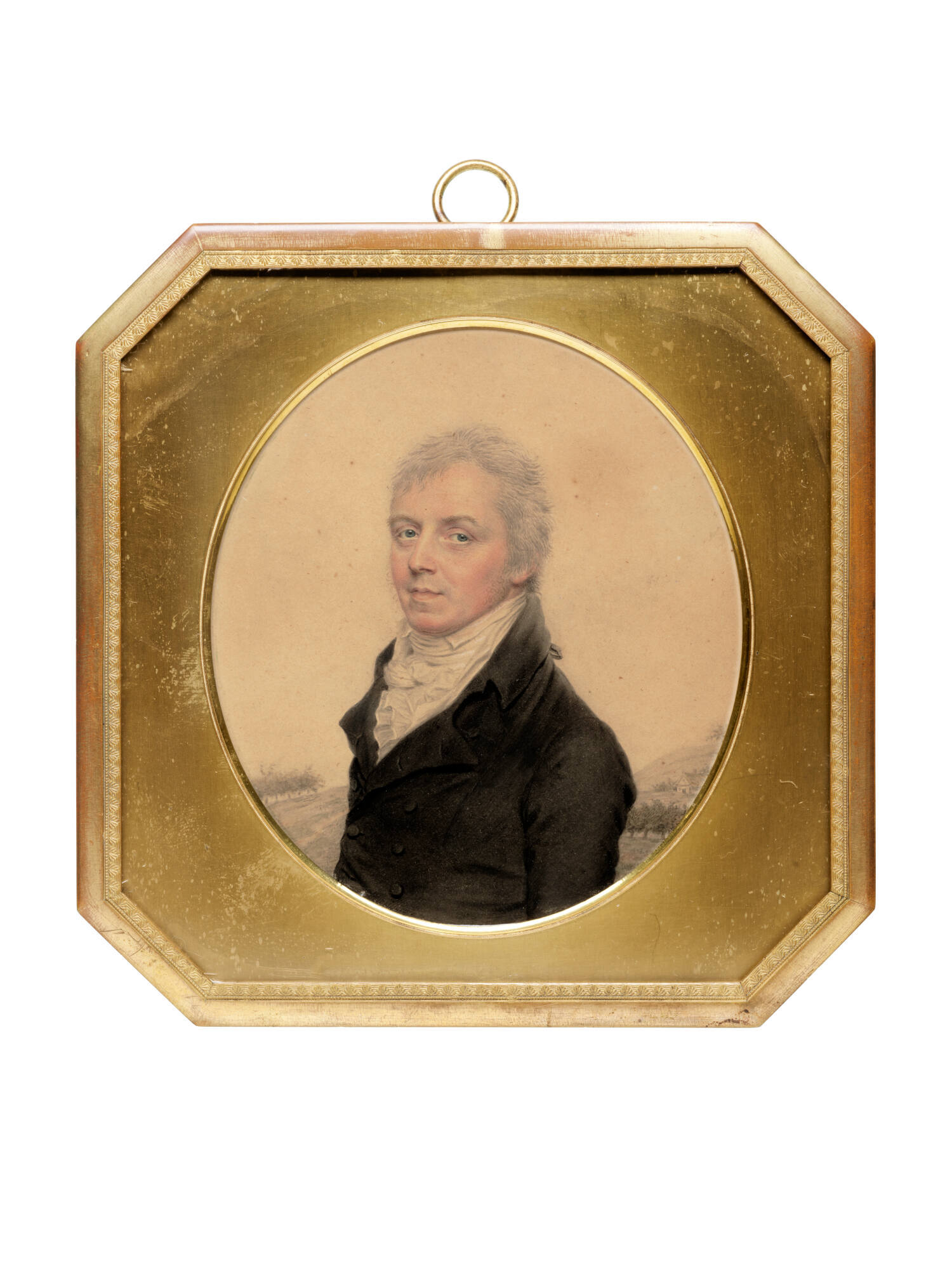

Portrait of a Woman

Framed: 6 × 4 7/8 inches (15.24 × 12.38 cm)

High-waisted flowing dresses and unpowdered curls abounded in the Regency era (about 1795-1837). A period in Britain associated with the rise of King George IV and the work of novelist Jane Austen, this time left its mark on fashion, too.

Inspired by the classical fashions of Greece and Rome, this period witnessed an emphasis on elegance and simplicity. Recalling garments on ancient statues, women often wore lightweight white fabrics closely fitted to the torso, with waistlines falling just under the bust. This style, known as Empire waist, initially appeared in France and England in the 1790s and gained currency during Napoleon's empire (1804-1814), as reflected in its name. It continues to appear in fashions today.

Amélie Levaigneur (née Grondard, 1824–1912), Paris, by 1912 [1];

Sold at her posthumous sale, Tableaux Anciens, Oeuvre Importante de Rembrandt Et Autres par J. Both, Thomas de Keyser, Jacob Ruysdael, Ph. Wouwerman, etc.; Tableaux Modernes par Diaz, Troyon, etc. . . . Dont La Vente Par suite du Décès de Madame Levaigneur, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, May 4, 1912, lot 242, as Portrait de femme [2];

Madame Dhainaut, Paris, by 1936 [3];

Purchased from her sale, Very Choice Collection of Works of Art, the Property of Madame Dhainaut of Paris, Sotheby and Co., London, December 10, 1936, lot 12, as An Attractive Miniature of a Lady, by Frost and Reed, London, probably on behalf of George Herbert Kemp (1886–1940), The Darlands, Totteridge, Hertfordshire, 1936–1940 [4];

Purchased at Kemp’s posthumous sale, Old English Silver, Fine Portrait Miniatures and Objects of Vertu, Sotheby’s, London, July 31, 1952, lot 114, as Lady by Leggatt Brothers, London, probably on behalf of Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, 1952–1958 [5];

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1958.

Notes

[1] With thanks to Bailey McCulloch for her assiduous research and discovery of the Levaigneur and Dhainaut provenance, and to Meghan Gray for further sleuthing. According to Levaigneur’s sales catalogue, she inherited the collection of her godfather, Théodore Dablin (1783–1861), to which she added her own purchases. For Dablin’s biography, see Antoine Maës, “L’illustre ascendance de Théodore Dablin: ‘Une famille de serruriers du roi’ à Rambouillet sous Louis XVI,” L’Année balzacienne 18, no. 1 (2017): 41–66.

[2] The miniature is illustrated as lot 242 of the Levaigneur sale and described as “Grande miniature ovale: Portrait de femme, en buste, vétue de blanc, portant une ceinture rose, coiffée d’un bonnet tuyauté orné de deux roses, par J. Isabey. Signée.”

[3] Madame Dhainaut remains unidentified, but her husband was the director of the casinos in Spa (from about 1889 until at least 1900) and Enghien-les-Bains (1906–1912), a chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur (1912), and he contributed money to the casino in Touquet-Paris-Plage. See Georges Bal, “La Curiosité,” New York Herald (May 18, 1924): 5. She was a widow by 1926 and living in Touquet-Paris-Plage. See “Deuil,” Journal de Montreuil et de l’arrondissement (August 22, 1926): 2. We have been unable to identify them further. However, she had a significant collection of decorative arts and portrait miniatures that are now spread across major private collections and museums, including the Wallace Collection, the British Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Walters Art Gallery, and the Nelson-Atkins. A Sèvres urn in the Nelson-Atkins collection also previously belonged to Madame Dhainaut (33-1580/2), https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/18208/urn.

[4] Ten miniatures belonging to “the late Herbert Kemp, Esq.” were sold at Sotheby’s in 1952, including this portrait, with the proceeds “sold on behalf of the Musicians’ Benevolent Fund,” which may be an avenue for future research on Mr. Kemp.

Notably, a miniature today in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, P.12-1940, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O81921/an-unknown-man-possibly-james-portrait-miniature-gibson-richard/, has a similar provenance. In 1935 (the year before the Dhainaut sale), Frost and Reed, a longstanding London art dealer, purchased that miniature on behalf of a Mr. G. H. Kemp from Christie’s, June 24, 1935, lot 51 (known at the time as by Lawrence Crosse, Portrait of Sir Robert Walpole). When G. H. Kemp died in 1940, his executors sold the miniature, again through Frost and Reed, to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. See John Murdoch, Seventeenth-Century English Miniatures (London: Stationery Office, 1997), 194. G. H. Kemp is also listed as the owner in 1938 of a miniature self-portrait by John Smart, now also in the V&A collection, P.11-1940, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O75215/miniature-self-portrait-of-john-portrait-miniature-smart-john/. See Ralph Edwards, “English Miniatures at the Louvre,” Burlington Magazine 72, no. 422 (May, 1938): 225.

Both “G. H. Kemp” and “Herbert Kemp, Esq.,” whose executors sold the Nelson-Atkins miniature in 1952, are most likely George Herbert Kemp, a biscuit magnate, who died on January 16, 1940. While a twelve-year gap between his death in 1940 and the 1952 sale is substantial, Kemp’s widow Margaret Prudence Kemp lived until 1959, and it is not improbable that Kemp’s executors assisted her with the sale of the miniatures later in her life. It may be of interest that a miniature of a “Mrs. Herbert Kemp” by Miss Edith Kemp-Welch was displayed in the forty-third annual exhibition of the Royal Society of Miniature Painters, Sculptors and Gravers at the Arlington Gallery, 22, Old Bond Street, in 1938, but the name was so common that they may not be related.

[5] Archival research indicates that the Starrs purchased many miniatures from Leggatt Brothers, either directly or with Leggatt acting as their purchasing agent.

Catalogue de Tableaux Anciens, Oeuvre Importante de Rembrandt Et Autres par J. Both, Thomas de Keyser, Jacob Ruysdael, Ph. Wouwerman, etc.; Tableaux Modernes par Diaz, Troyon, etc. . . . Dont La Vente Par suite du Décès de Madame Levaigneur (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, May 2–4, 1912), VIII, 54, (repro.), as Grande Miniature Ovale.

“Mouvement des Arts: Collection de feu Madame Levaigneur,” La Chronique des Arts et de la Curiosité, no. 19 (May 11, 1912): 151.

Catalogue of a Very Choice Collection of Works of Art: The Property of Madame Dhainaut of Paris (London: Sotheby and Co., December 10, 1936), 13, as An Attractive Miniature of a Lady.

Catalogue of Old English Silver, Fine Portrait Miniatures and Objects of Vertu (London: Sotheby and Co., July 31, 1952).

Art Prices Current (London: Art Trade Press, 1952), 29:171, as Lady.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 265, as Portrait of a Lady.

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 242, p. 79, (repro.), as Unknown Lady.

Blythe Sobol, “Jean-Baptiste Isabey, Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1825,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 1, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.2308.