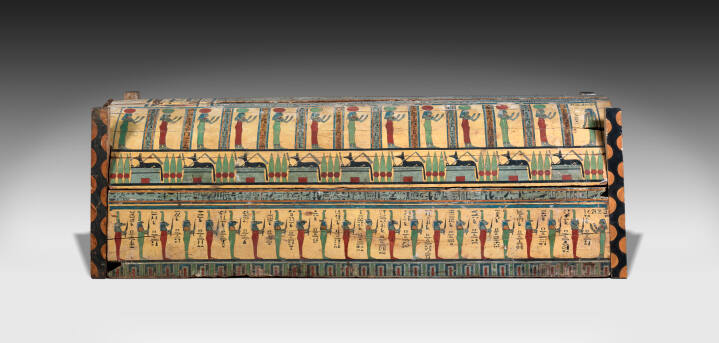

Muse Sarcophagus

- 104

In going through almost any modern cemetery one is struck by the anonymity of the dead: fields, crosses, a few inscriptions. Not so in the ancient Roman world. Aristocratic Roman families had large mausoleums within which were huge and elaborately carved marble sarcophagi (coffins). Members of the family would visit the inside of these mausoleums and see these sarcophagi on special memorial days for the deceased.

This sarcophagus was carved for a wealthy woman who wished to be shown among the Muses, the spirits who governed all cultural endeavors. Holding a scroll, the deceased stands in the middle of the Muses and their leader Minerva. All the figures can be identified by what they wear or by the musical instruments or other attributes that they hold. For instance, we know that the figure to the right of the deceased is Minerva since she carries a spear, wears a helmet, and has an aegis (a protective device) over her chest. On the other side of the deceased the Muse Terpsi-chore, who governed lyrical poetry, carries a large lyre. Griffins, winged lions who protect the deceased, appear on the narrow sides. Roman sarcophagi often depicted myths, battles, and even scenes from daily life.

Why did the deceased choose to portray herself among the Muses on this sarcophagus? Probably she wanted to show future generations that she was a cultured lady not interested simply in staying home and raising a family (among the few proper activities of a Roman woman). The imagery also suggests that she has passed from this world and found a place among the immortal Muses. She enjoys eternity because of her cultural achievements.

Excavated in the Vigna Casali, Rome, 1872 [1];

Giuseppe Scalambrini, Rome, by 1888;

His creditors’ sale, Collezione Scalambrini di Roma, Antichita greche e roame, sculture in marmi, musaici, bonzi, terre cotte, vetri, intagli, camei e medaglie …Appartenenti al Ceto Creditorio, Vincenzo Capobianchi, March 5, 1888, lot 1399;

Flora Whitney Miller (1897-1986), by 1986;

Purchased at her posthumous sale, Antiquities and Islamic Works of Art, Sotheby’s, New York, November 24, 1987, lot 154, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1987.

NOTES:

[1] E. Brizio, “Scavi: Scoperte nella vigna Casali,” Bullettino dell’Instituto di Correspondenza Archeologica (1873): 19-21 and Pietro Rosa, Sulle scoperte archeologiche della città e provincia di Roma, negli anni 1871-1872: Relazione (Rome: Regia Tipografia, 1873), 12. A sarcophagus with similar provenience and early provenance is in the Getty Museum collection, object number 83.AA.275.1.

E. Brizio, “Scavi: Scoperte nella vigna Casali,” Bullettino dell’Instituto di Correspondenza Archeologica (1873): 19-21.

Pietro Rosa, Sulle scoperte archeologiche della città e provincia di Roma, negli anni 1871-1872: Relazione (Rome: Regia Tipografia, 1873), 12.

Friedrich Matz and Friedrich Karl von Duhn, Antike Bildwerke in Rom mit Ausschluss der grösseren Sammlungen, vol. 2 (Leipzig: K. W. Hiersemann, 1881), 417-18, no. 3280.

Catalogo della Collezione Scalambrini di Roma…Appartenenti al Ceto Creditorio di Giuseppe Scalambrini (Rome: Vincenzo Campobianchi, 1888), unpag., (repro).

Max Wegner, Die Musensarkophage, Die antiken Sarkophagreliefs, Bd. 5, 3 Abt. (Berlin: Verlag Gebr. Mann, 1966), 76, no. 197.

Klaus Fittschen, review of Die Musensarkophage, by Max Wegner, Gnomon 44 (1972): 496-97.

Bernard Andreae and Helmut Jung, “Vorläufige tabellarische Übersicht über die Zeitstellung und Werkstattzugehörigkeit von 250 römischen Prunksarkophagen des 3. Jhs. n. Chr.,” Archäologischer Anzeiger, Heft 3 (1977): table after p. 434.

Ernst Rudolf, “Typologische Untersuchungen zu den stadtrömischen Musensarkophagen des 3. Jh. n. Chr.,” Marburger Winckelmann-Programm (1981): 42-43.

Huberta Heres, “Ein Verschollener Musensarkophag,“ Forschungen und Berichte 22, Archäologische Beiträge (1982), pp. 187-191.

Guntram Koch, Hellmut Sichtermann, and Friedrike Sinn-Henninger, Römische Sarkophage, Handbuch der Archäologie (Munich: C. H. Beck’sche, 1982), 199 (Koch).

Antiquities and Islamic Works of Art (New York: Sotheby’s, November 24-25, 1987), lot 154.

Souren Melikian, “Surprise, Surprise,” Art and Auction 10, no. 7 (February 1988): 82.

Helen-Louise Seggerman, “Antiquities, New York, Sotheby’s,” Art and Auction 10, no. 8 (March 1988): 129.

Guntram Koch and Karol Wight, Roman Funerary Sculpture: Catalogue of the Collections (Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1988), 46.

Donald Hoffmann, “Nelson Gallery adds Roman sarcophagus,” Kansas City Star, December 24, 1989.

Rita Santolini Giordani, Antichità Casali: La collezione di Villa Casali, Studi Miscellanei 27 (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider: 1989), 73-74, 136-37, no. 89.

Robert Cohon, “Hesiod and the Order and Naming of the Muses in Hellenistic Art,” Boreas 14/15 (1991/1992): 70n15.

Robert Cohon, “A Muse Sarcophagus in Its Context,” Archäologischer Anzeiger, Heft 1 (1992): 109-19.

Jan Stubbe Østergaard, “En romersk sarkofag med løwejagt,” Meddeleser fra Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek (1994): 94, figs. 20-23.

Jan Stubbe Østergaard, “Metropolitan Roman Sarcophagi in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen,” in Akten des Symposiums “125 Jahre Sarkophag-Corpus,” Marburg, 4.-7. Oktober 1995 , Sarkophag-Studien, Bd. 1, ed. Guntram Koch (Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1998), 98.

Björn Christian Ewald, Der Philosoph als Leitbild: Ikonographische Untersuchungen an römischen Sarkophagreliefs , Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archölogischen Instituts, roemische Abteilung, Vierunddreissigstes Ergänzungsheft (Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, 1999), 11n11, 35, 128, 148-50, (B 3), plate 21. 1-3.

Henning Wrede, Senatorische Sarkophage Roms: Der Beitrag des Senatorenstandes zur römischen Kunst der hohen und späten Kaiserzeit , Monumenta Artis Romanae 29 (Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 2001), 101.

Stine Birk “Carving sarcophagi: Roman sculptural workshop and their organisation,” in Ateliers and artisans in Roman art and archaeology, ed. Troels Myrup Kristensen and Birte Poulsen, Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 92 (Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 2012), 56.

Barbara Borg, Crisis and ambition: Tombs and burial customs in third-century CE Rome (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 126-30, 181, 224.

Robert Cohon with Xing Song, “The Hesiodic Order in Roman Sarcophagi,” Boreas 37/38 (2014-2015), in print.

Julian Zugazagoitia and Laura Spencer. Director's Highlights: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Celebrating 90 Years, ed. Kaitlyn Bunch (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), 124-125, (repro.).